Lecture Date: August 25, 2020

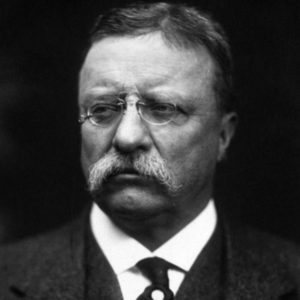

Few presidents have been more beloved than Theodore Roosevelt. As the first president elected in the 20th century, he has been called the “first modern president”—an appropriate description, both in terms of his politics and his personality.

TR was, and remains, the youngest person to ever serve as president, assuming the office upon the assassination of William McKinley in 1901. (JFK was the youngest man ever elected to office.)

Roosevelt embodied a host of contradictions. He was, for example, a sickly, asthmatic child who emerged in the popular imagination as a symbol of robust masculinity.

He was an historian and author who also was an advocate of the “strenuous life” and contemptuous of effete intellectuals (read: Woodrow Wilson).

He was an ardent conservationist who was also an avid big-game hunter.

The most pugnacious of presidents, who became famous as Colonel Roosevelt leading his volunteer “Rough-Rider” regiment during the Spanish-American War, he also won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to end the Russo–Japanese War.

Most ironically of all, although coming from a background of aristocratic privilege, TR emerged as the foremost leader of a populistic reform program—and did so from within the theretofore staunchly conservative Republican Party.

At a time when government involvement in social and economic affairs was negligible, he worked to implement anti-trust legislation and led the movement to enact business regulations, conservation initiatives, and consumer protection laws.

In foreign policy his achievements were mixed, the most significant being the construction of the Panama Canal. Not so admirable was his promulgation of the so-called “Roosevelt Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine, by which the U.S. arrogated to itself the right to intervene in Latin American affairs—a policy that engendered decades of suspicion and resentment in that region.

On the most controversial domestic issue of the day—women’s suffrage—Roosevelt was forthrightly supportive, declaring in his 1880 senior thesis at Harvard, “I think there can be no question that women should have equal rights with men.”

His racial views were more problematic. On the one hand, he earned plaudits from progressives (and enmity from Southern segregationists) for inviting Booker T. Washington to the White House.

On the other hand, his record was besmirched by his role in the Brownsville Affair, in which he summarily, and on flimsy evidence, issued dishonorable discharges to an entire company of black soldiers who were alleged to have been involved in a disturbance in that Texas town. (They were exonerated decades later, in the 1970s.)

Such occasional missteps notwithstanding, TR’s popularity remained essentially undiminished after almost two full terms. His Mount Rushmore legacy was secure, grounded mainly in his leadership of the progressive reform movement and its legislation, an achievement all the more remarkable considering the opposition of the conservative faction within his own party, as well as the prevailing laissez–faire, social Darwinist zeitgeist.

His progressive accomplishments were doubtlessly animated by the captivating appeal of his outsized personality. Americans, accustomed to bland, passive leadership in the White House, had never seen anything like the exuberant Roosevelt. He clearly gloried in the use of the “bully pulpit” to advance his agenda.

One observer aptly described him as “the Tom Sawyer of the political world, always looking for a chance to show off.” Citing his aphorism, “Speak softly and carry a big stick,” another mused that Roosevelt “carried a big stick all right, but the soft speaking resembled the bellowing of a bull moose during mating season.”

Some staid souls looked askance at such rambunctious behavior, but the public generally adored him, prompting poets Rosemary and Stephen Vincent Benet to write:

TR is spanking a Senato TR is chasing a bear.

TR is busting an awful trust and dragging it from its lair.

They’re calling TR a lot of things the men in the private car,

But the day coach likes exciting folks and the day coach likes TR.

Indeed they did, and continued to do so long after his death in 1919 -- his memory perpetuated by the presence of eponymous “Teddy bears” in the bedrooms of countless children forever after.

Perhaps one observer’s succinct comment on the passing of the Rough Rider summarized it best: “You had to hate the Colonel an awful lot,” he said, “not to love him.”

Published in the Free Lance-Star

August 23, 2020

Speaker: William B. Crawley

UMW Professor Emeritus of History

Director of Great Lives