Lecture Date: August 11, 2020

In recent years, as biographers have reinterpreted significant historical lives, there has been a tendency toward denigrating the reputations of a number of previously hallowed individuals.

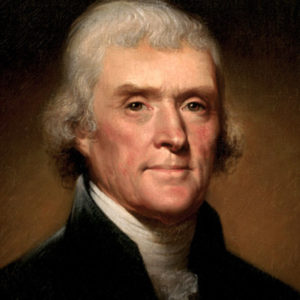

In this process -- referred to, sometimes derisively, as “revisionism” -- perhaps no figure in American history has suffered greater decline in stature than Thomas Jefferson.

To be sure, the third President had enemies in his own times, including one who ineloquently referred to him as a “son of a bitch” and a “red-headed rascal.” Others, in contrast, revered him as the “Sage of Monticello,” emphasizing his immortal precept that “all men are created equal.”

In a letter to James Madison dated February 17, 1826, Jefferson implored his friend and presidential successor to “take care of me when dead.” He need not have worried, at least for his immediate posterity. Indeed, for more than a century following his July 4, 1826 death, the preponderance of historical opinion -- either diminishing or ignoring altogether his involvement with slavery and his racist views – was so uniformly in Jefferson’s favor that one historian, writing in the 1940s, declared that “the enemies of Thomas Jefferson are all dead or else are in hiding.”

But with the coming of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 60s, biographers began to focus increasingly on his personal life, which presaged the end of Jefferson’s secular sainthood. One critic pointed out the irony that “the leisure that made possible Jefferson’s great writings on human liberty was supported by the labors of three generations of slaves.”

Accordingly, another went so far as to proclaim that “in the multi-racial American future, Jefferson will not be revered. . . .The sound you hear is the crashing of a reputation.”

Certainly Jefferson’s legacy is nothing if not complicated, rendered nearly inscrutable by the jarring juxtaposition of his words with his works. As one historian so aptly put it: “In the 19th century, abolitionists used Jefferson’s words as swords; slaveholders used his example as a shield.”

There can be no doubt that Jefferson did indeed hold views that most people today would justifiably consider racist. And he himself flatly stated in his Notes on Virginia (1795) that he suspected “blacks to be inferior to the whites.”

Yet despite those words—and, more pertinent still, his lifelong ownership of slaves -- there is evidence that he deplored the institution (at least in theory) and, unlike many of his contemporaries, did not extol the institution or employ presumed racial inferiority as justification for enslavement. “Whatever their degree of talent,” he wrote, “it is no measure of their rights.”

At the same time, it should be noted that his disapproval was apparently grounded more in the corrosive effect he believed the institution to inflict upon the white population than in its inhumanity to the blacks themselves. In particular, he feared the damage that it did to the industriousness of whites because, as he famously put it, “In a warm climate, no man will labor for himself who can make another labor for him.”

It should further be noted that Jefferson’s various plans for emancipation were invariably accompanied by the requirement that freed slaves be deported. Why so? Because he believed that “the two races, equally free, cannot live [under] the same government.” And any attempt to do so was fraught -- likely to “produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

Aside from Jefferson’s written and public pronouncements regarding slavery, the issue is rendered more problematic by his private actions including, most notoriously, the long-rumored relationship with his female slave Sally Hemings -- a liaison now widely presumed to have been true.

As time went on, Jefferson became increasingly discouraged on the slavery issue, concluding that emancipation “is not to be a work of my day.” And, of course, he was right. Yet he maintained a glimmer of hope, writing near the end of his life that “time, which outlives all things, will outlive this evil also.”

Surely Jefferson’s life was a complex one, and any attempt to analyze him raises the question of the extent to which revisionist interpretations should overwhelm an individual’s positive contributions – which in Jefferson’s case were considerable, among them the authorship of the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute on Religious Freedom; two terms as President; purchase of the Louisiana Territory; and founding of the University of Virginia.

Beyond that, and more generally, there is the matter of the propriety of judging historical figures by contemporary standards that are often at great variance from the times in which the biographical subject lived. In any case, as mores continue to evolve, the Jefferson debate proceeds undiminished -- and unresolved.

Published in the Free Lance-Star

August 9, 2020

Speaker: William B. Crawley

UMW Professor Emeritus of History

Director of the Great Lives