Lecture Date: September 8, 2020

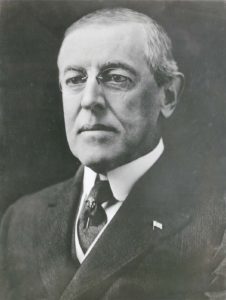

Woodrow Wilson, born in Staunton, Virginia, in 1856, became the first Southern-born President elected since the Civil War. He was the most highly educated, holding both a law degree and a doctorate in political science. He was the most overtly religious, save perhaps Jimmy Carter. And he was one of the most tragic.

In truth, Wilson was an unlikely candidate for the White House. Shy by nature, and coddled as an only child by his mother, he did not attend formal school until he was 13. But despite his reserve and lack of popular rapport, he was highly ambitious.

The central and determining influence on Wilson’s life was, unarguably, religion. He came by it naturally, particularly through his Presbyterian minister father. From him he imbibed not only religious conviction but a penchant for eloquence of expression, both oral and written.

For Wilson, religion was his constant guide. He prayed daily and gave thanks before every meal. He read the Bible every day, wearing out several in the course of his lifetime. All of this had both positive and, to the minds of many observers, negative effects. On the one hand, it sustained him in times of travail; on the other hand, it gave him an unbecoming (and often ineffective) sense of self-righteousness.

Having held faculty appointments at several universities, Wilson was elected governor of New Jersey in 1910 after serving as president of Princeton University. His success as a progressive reformer in that state won national attention, resulting in his Democratic nomination for President just two years later and election victory in 1912.

His enthusiasm for reform quickly translated to the federal level, which included establishment of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Trade Commission, tariff reduction, anti-trust legislation, implementation of a graduated federal income tax, and passage of the women’s suffrage amendment.

If history were to judge Wilson solely on his domestic accomplishments -- the most extensive in American history, save that of FDR’s New Deal and perhaps Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society -- he would be acknowledged as an extremely successful President.

Alas, with the advent of World War I, that was not to be the case. And it was his actions in that regard that led one critic to declare that Wilson was “not one of the world’s greatest men, but a great fiasco.”

His response to that war was complicated. At first he adamantly declared American neutrality, but as German provocations increased, he ultimately called upon Congress in April 1917 to declare war on the Central Powers. However, his ideals led him to elevate that action to the level of a great crusade -- one that would be, in his words, a “war to end war” and to “make the world safe for democracy.” And so doing, as it turns out, he promised far more than he was able to deliver.

In meeting with other allied leaders after the war, Wilson found that his idealistic plans for world peace were not necessarily shared by the Europeans, who were interested in more tangible sanctions against Germany. Ultimately, Wilson agreed to the Treaty of Versailles only if it included creation of a multi-national organization to address future disputes, namely, the League of Nations.

That prospect ran counter to a growing sense of isolationism at home, a sentiment that led to strenuous opposition to the Treaty in the Senate. Despite Wilson’s eloquent efforts in support, the Treaty never passed, largely because the rigidly self-righteous Wilson would not permit any compromise with regard to the League of Nations.

In the midst of the fight for the Treaty and League, Wilson, never physically robust, suffered a debilitating stroke in September 1919, which left him largely incapacitated for the remainder of his life.

Evaluations of Wilson have varied through the years, depending largely on the prevailing attitude toward internationalism at the time. The post-WWII creation of the United Nations, for example, reflected support for Wilson’s concept of international cooperation. When American intervention has been deemed overreaching (e.g., Vietnam), those principles have been disparaged.

Wilson himself would likely have been untroubled by such interpretive vicissitudes, so unshakable was his Presbyterian faith. He believed to the end that his behavior was not only correct, but righteous, remarking shortly before his death that he did not “have the least anxiety about the triumph of the principles for which I have stood” – adding with typical Wilsonian certitude, “That we [shall] prevail is as sure as that God reigns.”

Published in the Free Lance-Star

September 8, 2020

Speaker: William B. Crawley

UMW Professor Emeritus of History

Director of Great Lives