While his teammates tugged at their Speedos and swim caps, Dalton Herendeen had his own worries.

“It’s the first time my peers were going to see me without my leg,” he said of the start of middle school swim practice. “That’s scary.”

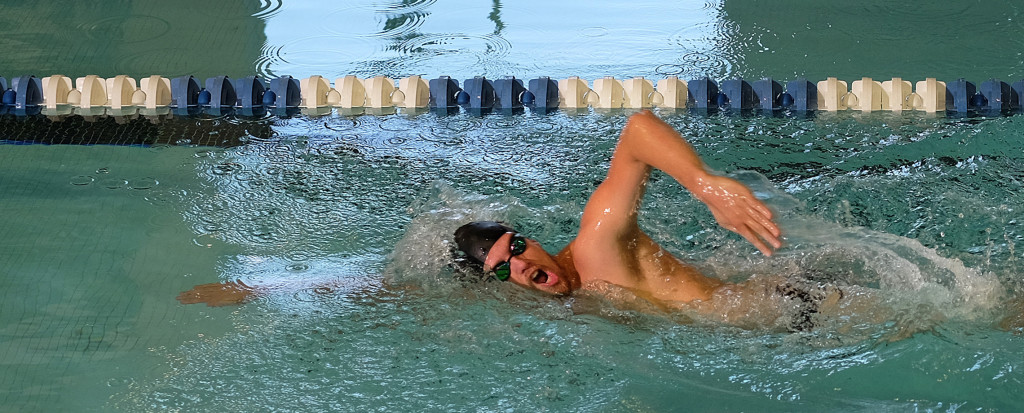

He took a deep breath, plunged into the pool and surfaced to a sight he would never forget: everyone staring, afraid to get in the water with him. He pled with his parents not to make him go back, but they wouldn’t budge.

UMW’s new assistant swim coach, Herendeen recounts the story from a Goolrick Hall lounge. When he shifts on the couch, there’s a slight clink of metal, his shorts showing his red, white and blue prosthetic leg. A U.S. Paralympic athlete and breaststroke record-holder, he’ll use his talent – and his story – to teach Mary Washington swimmers that no goal is too big.

“If you take away his disability, his story is similar to a lot of swimmers,” said Eagles head coach Abby Brethauer. “But he has a platform, and he’s willing to use it. He’s a great ambassador for the sport.”

Born with a blood clot near his left knee, Herendeen, now 22, put his parents in a precarious position. Removing the clot would risk his life. Amputation would not.

“You just don’t play those odds,” he said. He was 2 days old when he lost the lower half of his limb.

He’d struggle with a series of clunky prosthetics, while his parents, determined to treat him the same as his siblings, signed him up for sport after sport. In soccer, for example, “my leg would go farther than the ball,” Herendeen said. At 6-foot-4, he played basketball and football, but it was in the pool where he’d find his real niche.

He was a freshman when his coach at Indiana’s Concord Community High School suggested he look into Paralympics. Herendeen slammed the idea. He’d become a formidable opponent to full-bodied athletes; competing with handicapped swimmers seemed like a step backward.

The coach was persistent.

“Seeing legs and arms and wheelchairs and equipment all around the pool deck brought me back to reality,” Herendeen said of his first Paralympic meet in 2008.“I thought I was going to destroy these kids, but they were phenomenal. I got my butt kicked.”

He set his sights on making the 2012 U.S. team. While his friends hung out after school, binging on junk food, Herendeen ate, slept and breathed swimming.

By the time trials started at the London Aquatics Centre, he was a University of Indiana sophomore with a strong standing on its Division II team. This was where all his hard work would pay off. It was his day to shine. So when he watched his time in the backstroke creep onto the board, it blew him away. He’d missed the team by a hundredth of a second.

By the time trials started at the London Aquatics Centre, he was a University of Indiana sophomore with a strong standing on its Division II team. This was where all his hard work would pay off. It was his day to shine. So when he watched his time in the backstroke creep onto the board, it blew him away. He’d missed the team by a hundredth of a second.

“It was the worst, gutting feeling,” he said. “It was the hardest day of my life.”

Sleep never came in his hotel room that night. Instead, a never-ending nightmare, his performance running a loop inside of his mind. Herendeen would’ve rather stayed there the next morning than head back home with his parents. His family, his friends, his teammates, he’d let them all down.

They were on the plane – bags stowed, seatbelts fastened, ready for takeoff – when his phone rang.

“Dalton? Where are you?” It was U.S. Paralympic Swimming Director Queenie Nichols. “You better get back here. You made the team!”

In his despair, he’d forgotten the date. It was Father’s Day.

“That day on that plane I watched him cry for the first time in my life,” Herendeen said of his dad’s reaction to the news they still have a hard time believing.

He didn’t medal in London, but he gave it his all and did well. Back in the states and at college, though, something had changed. Just looking at water made him feel ill.

“I became a different person after London,” he said. “For the first time in my life, I didn’t have goals. I just wanted it to be over. I wanted to have a normal life.”

Once again a phone call – this one from UMW’s Brethauer – would pull him back to the pool. She’d seen Herendeen featured in the NCAA magazine Champion and wanted him to coach at the Bates College Swim Camp she co-founded.

Ten summer days there turned things around. Working with children pumped him back up, gave him purpose. He got back in the pool, broke lots of school records, became captain of his U-Indy team and one other thing: An exercise-science major, he switched career tracks from physical therapy to college coaching.

That’s when Brethauer, who’s helping him train for the 2016 Paralympics in Rio de Janeiro, started coaxing him toward Mary Washington.

“Coaching him has made me better because I have to think about things in different ways,” she said. “I think he’s going to make us all better.”

That’s Herendeen’s goal, both in and out of the pool. As a motivational speaker, he shares his experience at companies, camps and schools, with whoever will listen, including an early-October audience in UMW’s Dodd Auditorium.

“You look at my story and it’s awesome, but there are so many better stories out there,” he said. “Everyone’s disabled, whether you’re bad at math or nonathletic. I just struggle with walking. I like to take that message to the kids.”

Leave a Reply