Highlighting? Not allowed. Underlining? Don’t even think about it.

That was Caitie Finlayson’s approach to textbooks as a college student. As one of many undergrads who relied on financial aid, she kept pages pristine so the books could be resold for a small portion of the original – and often hefty – sum.

Years later, as an assistant professor of geography at UMW, Finlayson received a grant from the Center for Teaching Excellence and Innovation to revise her World Regional Geography course. She chose to write an open textbook that would make geography accessible to the masses – at no cost.

Two years later, her World Regional Geography textbook – published under an open license, which allows free sharing, editing, and reuse – has been downloaded over 2,000 times in over 30 countries. It has also been selected for inclusion in the eGranary Digital Library, which makes websites and digital education resources available to people in developing countries who might lack reliable internet access.

The geography textbook is part of a movement at UMW led by a group of faculty passionate about providing open educational resources (OER) in the classroom. Focusing specifically on open textbooks, the group – Open UMW – identifies existing open access resources and encourages faculty to either adopt them or create their own open textbooks.

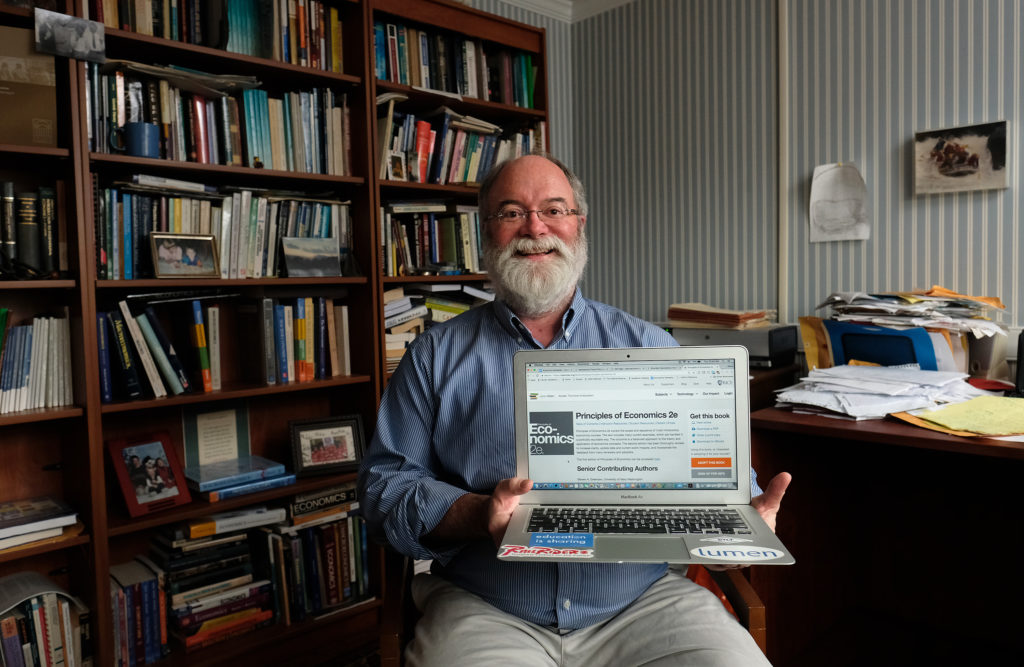

“You have potential to lose money when you publish openly,” said Steve Greenlaw, professor of economics and one of the university’s biggest champions of open access efforts. “But the good that you do is so much more than the money you would make anyway.”

And he would know.

Greenlaw’s open textbook, Principles of Economics, has been used by 152,722 students since it was published in 2014, according to the open textbook publisher OpenStax. That represents a $15 million savings, about $98 per book.

For some students, those savings make all the difference in their academic success.

“For students on financial aid, it’s common not to receive that aid until three weeks into the semester,” said Greenlaw, “If students don’t get the book until three weeks into the semester, they have a higher rate of failure because they fall behind.”

Continuing the Conversation at UMW

A recent survey of 110 UMW faculty showed that 86% are solely responsible for the selection of required textbooks in their classes, which illustrates the potential for OER to expand even further. That’s where UMW Libraries comes in.

In 2016, many of the Commonwealth of Virginia’s academic libraries joined the Open Textbook Network, a higher education initiative promoting OER that maintains the Open Textbook Library, an online catalog of open textbooks. As a network member, UMW Libraries provides workshops for faculty. Afterward, they can review a textbook from the library for a stipend.

“The workshops cover what open textbooks are, how they differ from e-textbooks provided by commercial publishers, and how textbook costs can impact student success,” said Erin Wysong, UMW reference and sciences librarian and UMW’s campus leader for the network. “My goal is to make sure UMW faculty are aware of all of their options when they select course materials.”

Wysong also addresses questions about quality, sharing that lower student textbook costs doesn’t have to come at the expense of quality.

“This isn’t a case of ‘you get what you pay for,’” Wysong said. “Studies have shown that students using OER have similar or better outcomes compared to students using traditional textbooks.”

In addition to the Open Textbook Library workshops, UMW Libraries has created an online guide to help faculty take a first step in looking for open educational resources for their courses.

“If just one faculty member decides to adopt an open textbook for a single class section, the aggregate cost savings for that section could be thousands of dollars,” Wysong said.

For Finlayson, who published World Regional Geography in 2016, open publishing breaks barriers to a subject she’s passionate about.

And Finlayson gets to see her students mark up the pages of their printable copy of the textbook – highlighters included. At $15 for a print copy, students are saving more than $100 on the textbook and can scribble away without worrying about the resale value.