Three became park rangers. Two became college professors. There was an artist and a geneticist, a veterinarian and a pharmacist. There were teachers and a tradeswoman, valedictorians and Fulbright scholars.

Milton Kline can tell you a story about each of them. He can tell you what their parents did and who they married, the early challenges of their careers and the places they settled: Arlington, Alaska, Seattle, Saudi Arabia and so many places in between.

Before they made a mark on the world, the University of Mary Washington’s student paint crew made a mark on him.

“Dumb lucky,” Kline will tell you about how it all came to be. “I got dumb lucky. Every day I came to work, I was greeted by motivated, energetic, smart people testing and practicing their life skills while working for me.”

There was a measure of happenstance to Kline’s 39-year college career that ended this month with the title “Professor Emeritus of Paintology.” How else to fully explain how a failed middle school teacher became the ultimate educator as the manager of the student painting program?

While they were teaching him—inspiring him with their minds, broadening his world view with their cultures and religions, moving him with their perseverance—Kline was teaching them, too.

Student

There would be no slacking between high school and college. Kline would have to get a summer job, his father, a school administrator who’d served in the South Pacific during World War II, told him. Kline could go work in the pickle factory or help his neighbor build houses.

“The construction job was the best thing that ever happened to me,” Kline said. “I did everything from digging the footing to putting the last shingle on the roof.”

When the summer was over, he headed to James Madison University, where he majored in health and physical education. His mother had taught kindergarten. His father had been a teacher, a coach, an assistant principal and the superintendent of King George County Schools.

Education may not have been what Kline loved. But it was what he knew. He took a job as a middle school teacher in Northumberland, Virginia. Six weeks later, he left.

“I couldn’t control the classroom,” Kline said. “I could have gone to France and done a better job and I couldn’t speak the language.”

It was 1975. Kline went back to construction. The work remained steady for nearly five years, until an economic recession hit. He needed a job. Mary Washington needed someone to fill a position inside its nine-member paint shop. It was the crew’s job to keep the campus looking fresh—from the residence halls to the president’s office.

“Dumb lucky,” Kline said again. “I guess if the guy across the street had run a barbershop, I’d be sweeping hair off the floor.”

Kline loved transforming a tired room into a gleaming masterpiece. It was not just a paycheck. It was the transformation, the feeling of accomplishment.

“People say they hate to paint. They just don’t know how. Nobody’s ever taught them,” he said.

Kline learned from the best college painters over the decades that followed—21 of them with a combined experience of some 500 years.

“I am a composite of all of those painters,” he said.

Teacher

By 1990, budgets were tightening. Buildings were also getting central air conditioning. Only Trinkle Hall had been equipped when Kline arrived in 1979.

Residence halls could wait for a fresh coat of paint. A malfunctioning HVAC system needed immediate attention.

“Same with electricians and plumbers,” Kline said.

As painters retired, their positions were reallocated. Someone floated the idea of student painters. A group was sent in to a residence hall, untrained and unsupervised. The results were disastrous. A student summer paint program was born, with Kline selected to manage it.

“I didn’t want any part of it. I didn’t think you could teach a student to paint in a summer.”

Kline still remembers then-President William Anderson’s command: Make the program an extension of their college learning experience. He remembers that first day, a dozen students sitting around waiting for him to tell them what to do.

He hired for the program the high achievers—the Eagle Scouts, the National Honor Society graduates, the captains of the football team. He looked for students who’d overcome hardship—a deaf student working on a music degree, an orphan, an immigrant, a childhood cancer survivor.

And then he gave them the Texas test: A series of questions designed to tell Kline whether he’d want to take a three-day car ride with them. It was immaterial to him whether they could paint. Only about 30 percent of the job was putting color onto a wall, anyway. He told them his goal was to make this the best job they ever had.

Inevitably, some were skilled artists. Others were not. He put them to work prepping rooms, or patching holes, or caulking cracks, or painting fire hydrants or lines on steps, which required little precision.

“I train everybody to be good at one thing,” he said, and nobody was better than Kline at figuring that out. He could do it by watching them for two or three minutes.

“I had one student who was six-foot-four. She was the tallest student I ever had. I was not going to have her painting baseboards,” Kline said.

People want to do what they’re good at. He knew that for a fact.

“I had to take a folk dance class in college. I don’t have the wire that runs from your head to your feet,” he said.

If he’d been bad at history, he could have sat in a corner and kept his mouth shut and his classmates would be none the wiser. In folk dance, his awkwardness was on full display day after day.

“It was unusual for me to get a partner. So I danced by myself. The walls were mirrored. It was pretty ugly,” Kline recalled.

He never forgot it. Never forgot how it felt to succeed. His student painters became fast and efficient. Over the years, the art of painting became a finely-tuned science, largely thanks to the innovative ideas of his students, Kline said. The summer program became year-round. Students lined up for a position.

No one on Milton Kline’s paint crew danced alone.

Professor

Painting, Kline will tell you, is like driving a car. Once you get the hang of it, you can do it while carrying on a conversation for hours. (Remember the Texas test?)

He listened. He learned. He learned that when students sat around not doing anything it wasn’t because they didn’t want to. It was because no one had ever taught them how to work, to look ahead, to stay busy.

He learned that making someone feel bad is no way to motivate them. That the best way to get consistency from a student who spent too much time on her cell phone was to challenge her to a race rather than call her out. For one day, she and Kline painted as many door jams as they could manage. She was expected to paint the same number every day after.

He taught them the value of making connections and encouraged them to find fun in the most mundane tasks. He taught his students to work to their own potential and not concern themselves with anybody else. He told them that the office manager was the single most important person to make friends with. That employers look for someone who can fit within their organization above all else.

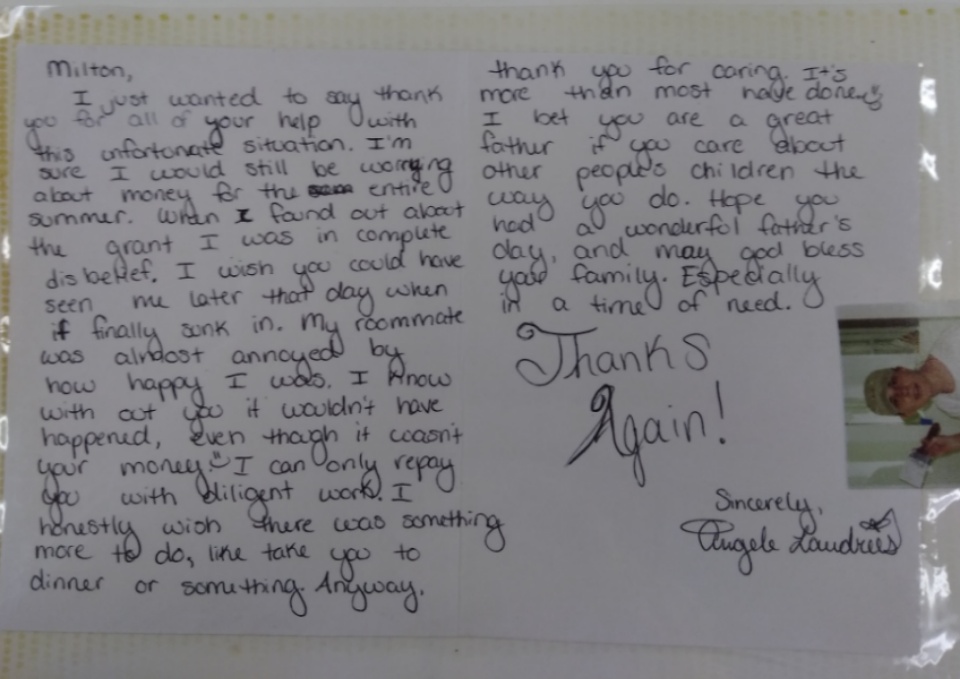

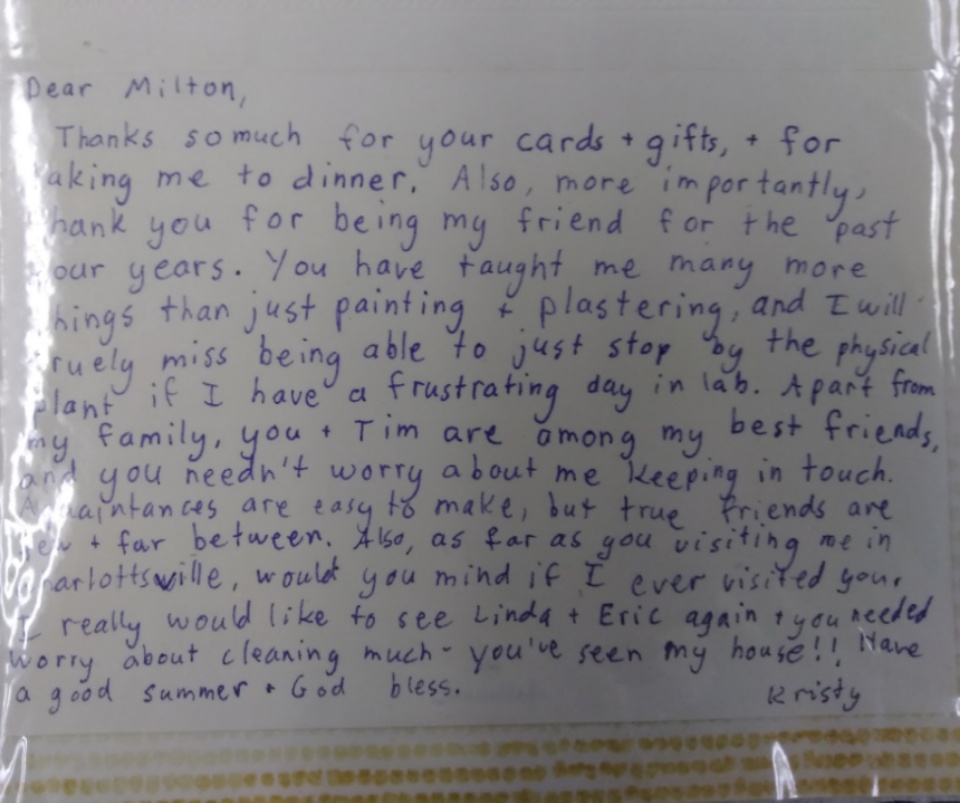

He attended their games and their research presentations, wrote them letters of recommendation and fielded phone calls and emails long after they graduated. He went to their weddings and asked after their pets and their parents.

When they were feeling uncertain about the future, Kline told them to make the best choice with the information they had.

“Sooner or later,” he told them, “it will all work out.”

Emeritus

For the first time in 25 years, Kline felt uncertain about the future.

He’d found his calling in the most unexpected place. Through sheer dumb luck, he said, he’d not only landed the best job at UMW—better than any professorship or presidency—he’d gotten the best Mary Washington education.

UMW felt the same way about him.

“With the heart of a teacher, he has mentored young adults for over a generation in life skills far beyond merely how to cut the corners of a room with a paint brush,” Associate Vice President for Facilities Services John Wiltenmuth said.

The proof was in the paint-spattered students who crowded among professors and administrators in the lobby of the Physical Plant last week to say goodbye—at least for now. Kline hopes to return part-time next year. First, he was heading to Europe with his wife, Linda, for a vacation that would include a stop in Nuremberg and Budapest to meet two of his former painters.

This was his final group of students. They spoke of his kindness, of how Kline seemed to care about them even before he hired them.

They spoke of the advice he’d given them, of the funny stories he told while they rolled ceilings and scraped walls and sanded patches. They said he was the best boss they ever had. They said this was the best job they ever had.

Kline had painted his masterpiece.

Fantastic. You can’t get this type of education at UVA, Tech, Harvard or Yale!

Milton was as important to these students in developing their character and life skills as any college class. Great legacy.

Milton very much deserved this honor, I think anyone who knows him would wish their children or grandchildren could have been a member of his paint crew. Mary Washington has certainly benefited from the mark he has made on these students and all who have known him.

Thank you, Kristin Davis, for a wonderful story about the painting legacy of Milton Kline at UMW. I fondly remember working as an elementary art teacher for his father. Milton is well deserving of appreciation for his dedication to UMW.