Rebecca Callaway ’19 could see the beauty in the broken.

Cracked and unusable, the donated concert harp came to her four months ago hardly worth the price it would cost to repair. But standing more than six feet tall, with an intricately carved column and crown, it was a dignified instrument Callaway had come to love.

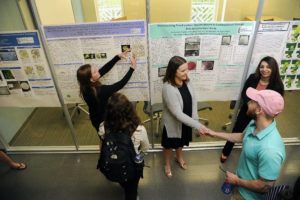

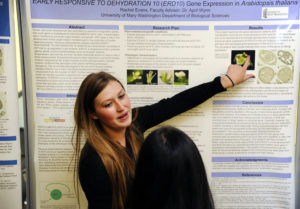

In the Hurley Convergence Center on Friday, she and University of Mary Washington classmate Mary Dye ’20 told the story of how they’d used modern technology to save it. Theirs was one of dozens of projects on display during UMW’s Research and Creativity Day, an annual celebration of student achievement across nearly every discipline.

All day Friday, students presented on topics as far-flung as fashion in France during the German Occupation and the potential of wind energy on the UMW campus.

Callaway and Dye’s work was somewhere in between, a marriage of art and science that used inexpensive electronic parts to make the old concert harp playable again. Hai Nguyen, physics professor and department chair, had taught students how to make laser pianos. Using lasers and circuitry, the students could create a tune by waving a hand rather than pressing a key.

Callaway, a physics and music performance major from Gloucester, Virginia, and Dye, a physics and music technology major from Clarksville, Tennessee, wanted to use the concept to inexpensively repair an instrument that might otherwise be unsalvageable.

The harp, which belonged to James Brooks Kuykendall, was nearly that. Rather than auction it off, the music professor donated the instrument to a pair of students with a plan.

A traditional repair would cost thousands of dollars. She and Dye could make the harp workable for less than $100.

It was a tedious process of soldering and mounting, of programming and coding. Under the guidance of Nguyen, the students slowly brought it back to life. It was a joy, the professor said, to work with students so dedicated and passionate

In the HCC on Friday, Callaway, who takes harp lessons from adjunct music instructor Grace Bauson, played a few simple tunes – “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb” – using what looked like invisible strings.

She and Dye say there is more work to be done, like making the notes sound more realistic. But they hope what they’ve done so far has broader implications.

“This injured harp has a new life in it now because Rebecca and Mary put so much care, time, and effort into it,” Nguyen said.

“I believe using modern technology, you could repair other instruments that would otherwise be thrown out or recycled,” Callaway said.

A steady flow of students came up to the harp and asked if they could play it. Then they ran their fingers through empty space and hear sound – and dashed off to send their friends over to try it.

“Oh, that is so cool,” said Daphne Ahalt ’18, a historic preservation major. “I want one of those in my house.”

A few feet away, Ahalt had set up her own project, the results of an archeological dig at a planation that housed a Union camp in the Civil War. Among her finds: a two-century old sticking tommy. The artifact had once been used to hold a candle, which Ahalt found fascinating.

But she could not stop talking about the harp.

“They took something very old,” she said, “and made it new again.”