It was a game-changing moment for Etan Thomas. Pulled over by the police, he sat silently on the road as an officer fixated on him. The policeman’s fingertips hovered over his holster, ready to grab his gun, while his partners tried to pinpoint why the black teen looked so familiar.

It must be from a mugshot, they said. When they demanded he pop his trunk, revealing high school basketball gear inside, they finally recognized the star athlete whose achievements were often splashed across the local newspaper.

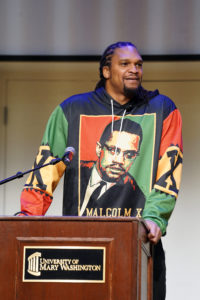

The former Washington Wizard shared that story during his Black History Month keynote Wednesday at the University of Mary Washington. Packed into the UC’s Chandler Ballroom, students, UMW athletes and coaches, faculty, staff, university administrators, President Troy Paino and wife Kelly, and community members listened raptly as Thomas discussed systemic racism, police brutality, the school-to-prison pipeline, stop-and-frisk and more. Thomas’ appearance came as the University celebrates Farmer Legacy 2020, honoring Dr. James L. Farmer Jr., the civil rights icon and late Mary Washington professor, who would have been 100 this year.

Thomas’ activism was borne out of that teenage incident, he said, buoyed by his mother’s passion for social justice, and a speech teacher who encouraged him to channel his emotions into an oratory, which he delivered at regional and national competitions, garnering media attention.

“I realized I could use this basketball thing to speak for people who can’t speak for themselves,” said Thomas, whose advocacy work earned him prestigious awards from the National Basketball Players Association and the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Foundation.

A published poet and author of several books, including 2018’s We Matter: Athletes and Activism, Thomas began the evening with a free-flowing, imagery-rich, spoken-word poem, which served as a springboard for the ensuing discussion.

In his poem, Thomas lamented the murders of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Terence Crutcher, Philando Castile and other victims of police brutality, as well as the pain felt by their families, whom Thomas interviewed for his book and supported in their quest for justice. He spoke of juries who failed to convict, politicians and pundits who attack athletes for speaking out against oppression and “a system that was built for us to fail.” Throughout, listeners snapped their fingers in agreement. Thomas’ poem ended with, “we are going to keep pursuing justice.”

UMW Women’s Lacrosse Assistant Coach Maddie Taghon asked about Colin Kaepernick – whom Thomas referenced in the poem – an NFL player publicly disparaged for taking a knee against systemic racism, corruption and police violence. By claiming that veterans and the National Anthem were the targets, Thomas said, the media and politicians discouraged other players from joining the protest. Changing the narrative took the focus off the real issue, he added.

Another question centered on the 1993 headline-making assertion by NBA Hall-of-Famer Charles Barkley that he was not a role model. Thomas took a different position. Young people will always look up to you, Thomas said, noting that his mother drilled that into him.

It’s been impactful, he said, when professional athletes have vocalized fears that their own children could become victims. Just like any other black parents, these athletes have to teach their children what to do if they are stopped by the police, he said. He shared his own harrowing experience of being pulled over with his teenage son, who was frustrated after watching his father record the interaction and politely ask the officer permission to reach for his wallet and registration on the dashboard.

“This isn’t about being fair,” Thomas told his son. “It’s about doing what we have to do in order to be safe.”

Engaging with people who have different experiences and perspectives is key, Thomas said. “For people to be able to understand and empathize with your reality, even if it’s not theirs, you need to create allies.”

Student Government Association President Jason Ford asked Thomas how to fight for others’ rights without losing focus on your own causes. Thomas’ response: “As you advocate on someone else’s behalf, make sure you ask them do the same for you.”

Juniors Makiah Faulks and Khalil Vest-Sims, leaders of UMW’s Black Student Association, both found the discussion inspiring. Like Thomas, Vest-Sims often kept his emotions bottled up, he said, until he discovered writing. Faulks is eager to share Thomas’ words of wisdom with her younger brothers.

“They’re also athletes,” she said, “and I want to show them that being an activist is cool.”